Abstract

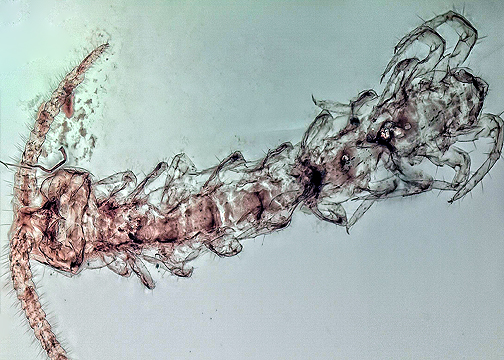

Chilopoda, part of Myriapoda, is a species-rich group of ~3300 formally described species. Yet, the phylogenetic relationship of centipedes is not fully clear, and the scarceness of their fossil record, compared to the closely related Diplopoda, is a major challenge for understanding their evolutionary history. Within Chilopoda, Lithobiomorpha is one of the most problematic concerning its fossil record, so far restricted to the Cenozoic (~40 mya) and with a single lithobiomorphan-like specimen from Kachin amber (~100 mya). Here, we report three new exceptionally well-preserved lithobiomorphan specimens from Myanmar amber (~100 mya). These represent the first report of oldest representatives of Henicopidae from the Cretaceous, and with this the oldest definite record of Lithobiomorpha. Two specimens have ten pairs of walking legs (stage IV), and one has a fully developed trunk. These specimens are similar in many aspects to the extant group of Henicopidae and, more precisely, to Lamyctes Meinert, 1868. The specimens seemingly lack ocelli, exhibit ~14 (stage IV) and 24 antenna articles, have 2+2 coxosternite teeth, and present tooth-like setae on their coxosternite margins (=porodont). The fully developed specimen possesses a tibial spinose projection on each tibia of legs 1–11, a blunt projection on the tibia of leg 12, and undivided tarsi on their legs 1–12. With the finding of these specimens, we expand the fossil record of Lithobiomorpha significantly.

References

- Anderson, J.M. (1975) The enigma of soil animal species diversity. In: Vaněk, J. (Ed.), Progress in soil zoology. Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences. Springer, Dordrecht, 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-010-1933-0_5

- Andersson, G. (1976) Post-embryonic development of Lithobius forficatus (L.), (Chilopoda: Lithobiidae). Insect Systematics & Evolution, 7 (3), 161–168. https://doi.org/10.1163/187631276X00270

- Andersson, G. (1979) On the use of larval characters in the classification of lithobiomorph centipedes (Chilopoda, Lithobiomorpha). In: Camatini, M. (Ed.), Myriapod biology. Academic Press, London, 73–81.

- Andersson, G. (1981) Post-embryonic development and geographical variation in Sweden of Lithobius crassipes L. Koch (Chilopoda: Lithobiidae). Insect Systematics & Evolution, 12 (4), 437–445. https://doi.org/10.1163/187631281X00517

- Andersson, G. (1984) Post-embryonic development of Lamyctes fulvicornis Meinert (Chilopoda: Henicopidae). Insect Systematics & Evolution, 15 (1), 9–14. https://doi.org/10.1163/187631284X00028

- Archey, G. (1937) Revision of the Chilopoda of New Zealand. Records of the Auckland Institute and Museum, 2 (2), 71–100. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42905967

- Attignon, S.E., Weibel, D., Lachat, T., Sinsin, B., Nagel, P. & Peveling, R. (2004) Leaf litter breakdown in natural and plantation forests of the Lama forest reserve in Benin. Applied Soil Ecology, 27 (2), 109–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2004.05.003

- Benavides, L.R., Edgecombe, G.D. & Giribet, G. (2023) Re-evaluating and dating myriapod diversification with phylotranscriptomics under a regime of dense taxon sampling. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 178, 107621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2022.107621

- Binyon, J. & Lewis, J.G.E. (1963) Physiological adaptations of two species of centipede (Chilopoda: Geophilomorpha) to life on the shore. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 43 (1), 49–55. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315400005221

- Bonato, L. & Zapparoli, M. (2011) 16 Chilopoda–Geographical distribution. In: Minelli, A. (Ed.), Treatise on zoology-anatomy, taxonomy, biology. The Myriapoda, Volume 1. Brill, Leiden, The Netherlands, 327–337. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004188266_017

- Bonato, L., Edgecombe, G.D., Lewis, J.G.E., Minelli, A., Pereira, L.A., Shelley, R.M. & Zapparoli, M. (2010) A common terminology for the external anatomy of centipedes (Chilopoda). ZooKeys, 69, 17–51. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.69.737

- Bonato, L., Edgecombe, G.D. & Minelli, A. (2014) Geophilomorph centipedes from the Cretaceous amber of Burma. Palaeontology, 57 (1), 97–110. https://doi.org/10.1111/pala.12051

- Bonato, L., Minelli, A., Drago, L. & Pereira, L.A. (2015) The phylogenetic position of Dinogeophilus and a new evolutionary framework for the smallest epimorphic centipedes (Chilopoda: Epimorpha). Contributions to Zoology, 84 (3), 237–253. https://doi.org/10.1163/18759866-08403004

- Bortolin, F. (2010) Genetic control of moulting and segmentation during post-embryonic development in Lithobius peregrinus (Chilopoda, Lithobiomorpha) [Doctoral dissertation, Università degli Studi di Padova]. Padua Research Archive.

- Brölemann, H.W. (1930) Éléments d’une faune des Myriapodes de France: Chilopodes. Imprimerie Toulousaine [Lion et Fils], Toulouse, 434 pp.

- Chagas-Jr, A. & Bichuette, M.E. (2018) A synopsis of centipedes in Brazilian caves: hidden species diversity that needs conservation (Myriapoda, Chilopoda). ZooKeys, 737, 13–56. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.737.20307

- Cruickshank, R.D. & Ko, K. (2003) Geology of an amber locality in the Hukawng Valley, northern Myanmar. Journal of Asian earth Sciences, 21 (5), 441–455. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1367-9120(02)00044-5

- Decaëns, T., Jiménez, J.J., Gioia, C., Measey, G.J. & Lavelle, P. (2006) The values of soil animals for conservation biology. European Journal of Soil Biology, 42, S23–S38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejsobi.2006.07.001

- Decker, P., Reip, H. & Voigtländer, K. (2014) Millipedes and centipedes in German greenhouses (Myriapoda: Diplopoda: Chilopoda). Biodiversity Data Journal, 2, e1066. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.2.e1066

- Deimezis-Tsikoutas, A., Kapsalas, G. & Pafilis, P. (2020) A rare case of saurophagy by Scolopendra cingulata (Chilopoda: Scolopendridae) in the central Aegean archipelago: A role for insularity? Zoology and Ecology, 30 (1), 48–51. https://doi.org/10.35513/21658005.2020.1.6

- Edgecombe, G.D. (2001) Revision of Paralamyctes (Chilopoda: Lithobiomorpha: Henicopidae), with six new species from eastern Australia. Records of the Australian Museum, 53 (2), 201–241. https://doi.org/10.3853/j.0067-1975.53.2001.1328

- Edgecombe, G.D. (2007) Centipede systematics: progress and problems. Zootaxa, 1668, 327–341. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.1668.1.17

- Edgecombe, G.D. (2011a) 1 Phylogenetic relationships of Myriapoda. In: Minelli, A. (Ed.), Treatise on Zoology-Anatomy, Taxonomy, Biology. The Myriapoda, Volume 1. Brill, Leiden, The Netherlands, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004188266_002

- Edgecombe, G.D. (2011b) 18 Chilopoda—Fossil history. In: Minelli, A. (Ed.), Treatise on Zoology-Anatomy, Taxonomy, Biology. The Myriapoda, Volume 1. Brill, Leiden, The Netherlands, 355–361. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004188266_019

- Edgecombe, G.D. & Giribet, G. (2003) Relationships of Henicopidae (Chilopoda: Lithobiomorpha): New molecular data, classification and biogeography. African Invertebrates, 44 (1), 13–38.

- Edgecombe, G.D. & Giribet, G. (2007) Evolutionary biology of centipedes (Myriapoda: Chilopoda). Annual Review of Entomology, 52 (1), 151–170. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ento.52.110405.091326

- Edgecombe, G.D., Giribet, G. & Wheeler, W.C. (2002) Phylogeny of Henicopidae (Chilopoda: Lithobiomorpha): a combined analysis of morphology and five molecular loci. Systematic Entomology, 27 (1), 31–64. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0307-6970.2001.00163.x

- Edgecombe, G.D., Strange, S.E., Popovici, G., West, T. & Vahtera, V. (2023) An Eocene fossil plutoniumid centipede: a new species of Theatops from Baltic Amber (Chilopoda: Scolopendromorpha). Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, 21 (1), 2228796. https://doi.org/10.1080/14772019.2023.2228796

- Eitzinger, B., Micic, A., Körner, M., Traugott, M. & Scheu, S. (2013) Unveiling soil food web links: New PCR assays for detection of prey DNA in the gut of soil arthropod predators. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 57, 943–945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2012.09.001

- Enghoff, H., Akkari, N. & Pedersen, J. (2013) Aliquid novi ex Africa? Lamyctes africanus (Porath, 1871) found in Europe (Chilopoda: Lithobiomorpha: Henicopidae). Journal of Natural History, 47 (31-32), 2071–2094. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222933.2012.763062

- Fernández, R., Laumer, C.E., Vahtera, V., Libro, S., Kaluziak, S., Sharma, P.P., Pérez-Porro, A. R., Edgecombe, G.D. & Giribet, G. (2014) Evaluating topological conflict in centipede phylogeny using transcriptomic data sets. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 31 (6), 1500–1513. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msu108

- Fernández, R., Edgecombe, G.D. & Giribet, G. (2016) Exploring phylogenetic relationships within Myriapoda and the effects of matrix composition and occupancy on phylogenomic reconstruction. Systematic Biology, 65 (5), 871–889. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syw041

- Fernández, R., Edgecombe, G.D. & Giribet, G. (2018). Phylogenomics illuminates the backbone of the Myriapoda Tree of Life and reconciles morphological and molecular phylogenies. Scientific Reports, 8 (1), 83, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-18562-w

- Folly, H., Thaler, R., Adams, G.B. & Pereira, E.A. (2019) Predation on Scinax fuscovarius (Anura, Hylidae) by Scolopendra sp. (Chilopoda: Scholopendridae) in the state of Tocantins, central Brazil. Revista Latinoamericana de Herpetología, 2 (1), 39–43. https://doi.org/10.22201/fc.25942158e.2019.1.43

- GBIF.org (2020) GBIF Home Page. Available from: https://www.gbif.org (accessed 13 January 2020)

- Gonzalez, A., Rodrigez-Acosta, A., Gassette, J., Ghisoli, M., Sanabria, E. & Reyez-Lugo, M. (2000) Bioecological aspects of Scolopendra (Scolopendra gigantea Linnaeus 1758) and the histopathological activity of its venom. Revista Cientifica, Facultad de Ciencias Veterinarias, Universidad Del Zulia, 10 (4), 303–309.

- Grimaldi, D.A., Engel, M.S. & Nascimbene, P.C. (2002) Fossiliferous Cretaceous amber from Myanmar (Burma): its rediscovery, biotic diversity, and paleontological significance. American Museum Novitates, 2002 (3361), 1–71. https://doi.org/10.1206/0003-0082(2002)361<0001:FCAFMB>2.0.CO;2

- Günther, B., Rall, B.C., Ferlian, O., Scheu, S. & Eitzinger, B. (2014) Variations in prey consumption of centipede predators in forest soils as indicated by molecular gut content analysis. Nordic Society Oikos, 123 (10), 1192–1198. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0706.2013.00868.x

- Harzsch, S. (2006) Neurophylogeny: Architecture of the nervous system and a fresh view on arthropod phylogeny. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 46 (2), 162–194. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/icj011

- Harzsch, S., Melzer, R.R. & Müller, C.H.G. (2007). Mechanisms of eye development and evolution of the arthropod visual system: The lateral eyes of Myriapoda are not modified insect ommatidia. Organisms Diversity and Evolution, 7 (1), 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ode.2006.02.004

- Haug, G.T., Haug, J.T. & Haug, C. (2024) Convergent evolution of defensive appendages—a lithobiomorph-like centipede with a scolopendromorph-type ultimate leg from about 100 million-year-old amber. Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments, 104, 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12549-023-00581-3

- Haug, J.T., Müller, C.H.G. & Sombke, A. (2013) A centipede nymph in Baltic amber and a new approach to document amber fossils. Organisms Diversity and Evolution, 13 (3), 425–432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13127-013-0129-3

- Haug, J.T., Haug, C., Schweigert, G. & Sombke, A. (2014) The evolution of centipede venom claws—open questions and possible answers. Arthropod Structure & Development, 43 (1), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asd.2013.10.006

- Hug, L.A. & Roger, A.J. (2007) The impact of fossils and taxon sampling on ancient molecular dating analyses. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 24 (8), 1889–1897. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msm115

- Hwang, U.W., Friedrich, M., Tautz, D., Park, C.J. & Kim, W. (2001) Mitochondrial protein phylogeny joins myriapods with chelicerates. Nature, 413 (6852), 154–157. https://doi.org/10.1038/35093090

- Iorio, É., Labroche, A. & Jacquemin, G. (2022) Les chilopodes (Chilopoda) de la moitié nord de la France : toutes les bases pour débuter l’étude de ce groupe et identifier facilement les espèces. Version 2. Invertébrés Armoricains, France, Rennes, 90 pp.

- Juen, A. & Traugott, M. (2007) Revealing species-specific trophic links in soil food webs: Molecular identification of scarab predators. Molecular Ecology, 16 (7), 1545–1557. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03238.x

- Klarner, B., Winkelmann, H., Krashevska, V., Maraun, M., Widyastuti, R. & Scheu, S. (2017) Trophic niches, diversity and community composition of invertebrate top predators (Chilopoda) as affected by conversion of tropical lowland rainforest in Sumatra (Indonesia). PLoS ONE, 12 (8), e0180915. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0180915

- Kos, A., Delić, T., Kos, I., Kozel, P., Polak, S. & Zagmajster, M. (2023) The overview of lithobiomorph centipedes (Chilopoda, Lithobiomorpha) from caves of Slovenia. Subterranean Biology, 45, 165–185. https://doi.org/10.3897/subtbiol.45.101430

- Kraus, O. (1974) On the morphology of Palaeozoic diplopods. In: Blower, G.J. (Ed.), Myriapoda. Second international Congress of Myriapodology. Symposia of the Zoological Society of London, London, 32, 13–22.

- Littlewood, P.M.H. (1983) Fine structure and function of the coxal glands of lithobiomorph centipedes: Lithobius forficatus and L. crassipes (Chilopoda, Lithobiidae). Journal of morphology, 177 (2), 157–179. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmor.1051770204

- Madzaric, S., Ceglie, F.G., Depalo, L., Al Bitar, L., Mimiola, G., Tittarelli, F. & Burgio, G. (2018) Organic vs. organic—Soil arthropods as bioindicators of ecological sustainability in greenhouse system experiment under Mediterranean conditions. Bulletin of Entomological Research, 108 (5), 625–635. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007485317001158

- Mao, Y.Y., Liang, K., Su, Y.T., Li, J.G., Rao, X., Zhang, H., Xia, F.Y., Fu, Y.Z. Cai, C.Y. & Huang, D.Y. (2018) Various amberground marine animals on Burmese amber with discussions on its age. Palaeoentomology, 1 (1), 91–103. https://doi.org/10.11646/palaeoentomology.1.1.11

- Menta, C. & Remelli, S. (2020) Soil health and arthropods: From complex system to worthwhile investigation. Insects, 11 (1), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects11010054

- Minelli, A. & Fusco, G. (2013) Arthropod post-embryonic development. In: Minelli, A., Boxshall, G. & Fusco, G. (Eds), Arthropod biology and evolution: molecules, development, morphology. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 91–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-36160-9_5

- Minelli, A. & Koch, M. (2011) 3 Chilopoda—General morphology. In: Minelli, A. (Ed.), Treatise on Zoology-Anatomy, Taxonomy, Biology. The Myriapoda, Volume 1. Brill, Leiden, The Netherlands, 43–66. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004188266_004

- Minelli, A. & Sombke, A. (2011) 14 Chilopoda—Development. In: Minelli, A. (Ed.), Treatise on Zoology-Anatomy, Taxonomy, Biology. The Myriapoda, Volume 1. Brill, Leiden, the Netherlands, 295–308. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004188266_015

- Molinari, J., Gutiérrez, E.E., Ascenção, A.A., Nassar, J.M., Arends, A. & Márquez, R.J. (2005) Predation by giant centipedes, Scolopendra gigantea, on three species of bats in a Venezuelan cave. Caribbean Journal of Science, 41 (2), 340–346.

- Moore, J. (2006) Chapter 14—Chelicerata and Myriapoda. In: Moore, J. (Ed.), An introduction to the invertebrates, 2. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom, 181–191. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511754760.015

- Müller, C.H. & Meyer-Rochow, V.B. (2006) Fine structural description of the lateral ocellus of Craterostigmus tasmanianus Pocock, 1902 (Chilopoda: Craterostigmomorpha) and phylogenetic considerations. Journal of Morphology, 267 (7), 850–865. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmor.10444

- Murienne, J., Edgecombe, G.D. & Giribet, G. (2010) Including secondary structure, fossils and molecular dating in the centipede tree of life. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 57 (1), 301–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2010.06.022

- Near, T.J. & Sanderson, M.J. (2004) Assessing the quality of molecular divergence time estimates by fossil calibrations and fossil–based model selection. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series B: Biological Sciences, 359 (1450), 1477–1483. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2004.1523

- Penney, D. (2010) Biodiversity of fossils in amber from the major world deposits. Siri Scientific Press, Manchester, 304 pp.

- Pérez-Gelabert, D.E. & Edgecombe, G.D. (2013) Scutigeromorph centipedes (Chilopoda: Scutigeromorpha) of the Dominican Republic, La Hispaniola. Novitates Caribaea, 6, 36–44. https://doi.org/10.33800/nc.v0i6.105

- Perrichot, V., Néraudeau, D., Nel, A. & De Ploëg, G. (2007) A reassessment of the Cretaceous amber deposits from France and their palaeontological significance. African Invertebrates, 48 (1), 213–227.

- Poser, T. (1988) Chilopoden als Prädatoren in einem Laubwald. Pedobiologia, 31 (3-4), 261–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-4056(23)02268-0

- Rasnitsyn, A.P. (1996) Burmese amber at the Natural History Museum. Inclusion, 23, 19–21.

- Ross, A.J. (2019) Burmese (Myanmar) amber checklist and bibliography 2018. Palaeoentomology, 2 (1), 22–84. https://doi.org/10.11646/palaeoentomology.2.1.5

- Schreiner, A., Decker, P., Hannig, K. & Schwerk, A. (2012) Millipede and centipede (Myriapoda: Diplopoda, Chilopoda) assemblages in secondary succession: Variance and abundance in Western German beech and coniferous forests as compared to fallow ground. Web Ecology, 12, 9–17. https://doi.org/10.5194/we-12-9-2012

- Shear, W.A. (2018) The centipede family Anopsobiidae new to North America, with the description of a new genus and species and notes on the Henicopidae of North America and the Anopsobiidae of the Northern Hemisphere (Chilopoda, Lithobiomorpha). Zootaxa, 4422 (2), 259–283. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4422.2.6

- Shear, W.A. & Bonamo, P.M. (1988) Devonobiomorpha, A new order of centipeds (Chilopoda) from the middle Devonian of Gilboa, New York State, USA, and the phylogeny of centiped orders. American Museum of Natural History, 1–30.

- Shear, W.A. & Bonamo, P.M. (1990) Fossil centipedes from the Devonian of New York State, USA. In: Minelli, A. (Ed.), Proceedings of the 7th International Congress of Myriapodology. Brill, Leiden, The Netherlands, 89–96. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004630383_014

- Shear, W.A. & Edgecombe, G.D. (2010) The geological record and phylogeny of the Myriapoda. Arthropod Structure and Development, 39 (2-3), 174–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asd.2009.11.002

- Shear, W.A., Jeram, A.J. & Selden, P. (1998) Centiped legs (Arthropoda, Chilopoda, Scutigeromorpha) from the Silurian and Devonian of Britain and the Devonian of North America. American Museum novitates, 3231, 1–16.

- Shi, G., Grimaldi, D.A., Harlow, G.E., Wang, J., Wang, J., Yang, M., Lei, W., Li, Q. & Li, X. (2012) Age constraint on Burmese amber based on U-Pb dating of zircons. Cretaceous research, 37, 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cretres.2012.03.014

- Smith, R.D. & Ross, A.J. (2016) Amberground pholadid bivalve borings and inclusions in Burmese amber: implications for proximity of resin-producing forests to brackish waters, and the age of the amber. Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 107 (2-3), 239–247. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755691017000287

- Stoev, P. (2002) A Catalogue and key to the centipedes (Chilopoda) of Bulgaria. Pensoft, Sofia, Moscow, 103 pp.

- Stoev, P., Akkari, N., Komericki, A., Edgecombe, G. & Bonato, L. (2015) At the end of the rope: Geophilus hadesi sp. n.—the world’s deepest cave-dwelling centipede (Chilopoda, Geophilomorpha, Geophilidae). ZooKeys, 510, 95–114. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.510.9614

- Stojanović, D.Z., Antić, D.Ž. & Makarov, S.E. (2021) A new cave-dwelling centipede species from Croatia (Chilopoda: Lithobiomorpha: Lithobiidae). Revue Suisse de Zoologie, 128 (2), 425–438. https://doi.org/10.35929/RSZ.0054

- Verhoeff, K.W. (1905) Über Scutigeriden. Zoologischer Anzeiger, 29, 73–119.

- Voigtländer, K. (2007) The life cycle of Lithobius mutabilis L. Koch, 1862 (Myriapoda: Chilopoda). Bonner Zoologische Beiträge, 55, 9–25.

- Voigtländer, K. (2011) 15 Chilopoda—Ecology. In: Minelli, A. (Ed.), Treatise on Zoology-Anatomy, Taxonomy, Biology. The Myriapoda, Volume 1. Brill, Leiden, The Netherlands, 309–325. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004188266_016

- Wesener, T. & Moritz, L. (2018) Checklist of the Myriapoda in Cretaceous burmese amber and a correction of the Myriapoda identified by Zhang (2017), Check List, 14 (6), 1131–1140. https://doi.org/10.15560/14.6.1131

- Wolfe, J.M., Daley, A.C., Legg, D.A. & Edgecombe, G.D. (2016) Fossil calibrations for the arthropod Tree of Life. Earth-Science Reviews, 160, 43–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2016.06.008

- Xing, L. & Qiu, L. (2020) Zircon U-Pb age constraints on the mid-Cretaceous Hkamti amber biota in northern Myanmar. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 558, 109960. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2020.109960

- Yu, T., Thomson, U., Mu, L., Ross, A., Kennedy, J., Broly, P., Xia, F., Zhang, H., Wang, B. & Dilcher, D. (2019) An ammonite trapped in Burmese amber. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116 (23), 11345–11350. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1821292116

- Zagmajster, M., Polak, S. & Fišer, C. (2021) Postojna-Planina cave system in Slovenia, a hotspot of subterranean biodiversity and a cradle of speleobiology. Diversity, 13 (6), 271. https://doi.org/10.3390/d13060271

- Zapparoli, M. & Edgecombe, G.D. (2011) 19 Chilopoda—Taxonomic overview. Lithobiomorpha. In: Minelli, A. (Ed.), Treatise on zoology–anatomy, taxonomy, biology—the Myriapoda, Volume 1. Brill, Leiden, The Netherlands, 371–389. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004188266_020

- Zhang, W.W. (2017) Frozen dimensions of the fossil insects and other invertebrates in amber. Chongqing University Press, Chongqing, China, 692 pp.